|

Bolton's Road to Revolution

April 19, 2025, marks the 250th anniversary of the battles at Lexington and Concord, the start of the American Revolution. The actions taken by the people of Bolton that led them to this monumental day were recorded in the Town’s meeting minutes as recorded in the Town of Bolton Record book. These stories are a result of our work with Freedom’s Way National Heritage Area’s Patriots’ Paths program under the mentorship of historian Mary Fuhrer. This is the story of Bolton’s Road to Revolution. View our theatrical production of Bolton's Road to Revolution here: https://bolton-ma.vod.castus.tv/vod/?video=4dceaca9-95e3-4a7e-96fe-049c35c655f5 |

|

The Stamp Act

The war for independence did not take the people of Bolton by surprise. For ten years prior, since 1765, they were debating and asserting their rights, protesting, petitioning, boycotting, assembling, preparing – and resisting. They came together to organize a provincial government, a treasury, a communication system, trained militia, arms, and even popular police control. They acted together as a town, and they made history.

In 1763, no people were prouder to be British than the country folk of Massachusetts. The British were recent victors in the French and Indian War – a war in which many Bolton men fought. Now they were part of the world’s greatest empire, and they could claim all the prized liberties of English subjects. But, a dozen years later, they were at war again. Only now they were Americans, and their enemy was the British.

Trouble began in the Fall of 1765. To raise money to pay for the recent war, Parliament ordered that all printed materials bear a taxed stamp. This Stamp Act was fiercely resisted. Colonists declared it violated their ancient right to have a say in any taxation. In Boston, mobs rioted. On August 12th mobs attacked Andrew Oliver’s home, the Massachusetts government official responsible for enacting the Stamp Act, and twelve days later a mob ransacked the home of Lieutenant Governor Thomas Hutchinson. In Braintree, John Adams eloquently laid out colonial grievances, instructing representatives to denounce the Stamp Act. More than forty other towns followed suit. The town of Bolton had its share of men who resisted this taxation, but the Reverend Thomas Goss, Bolton’s minister, preached that the people must defer and submit to their betters. And so, on the Stamp Act, Bolton was silent.

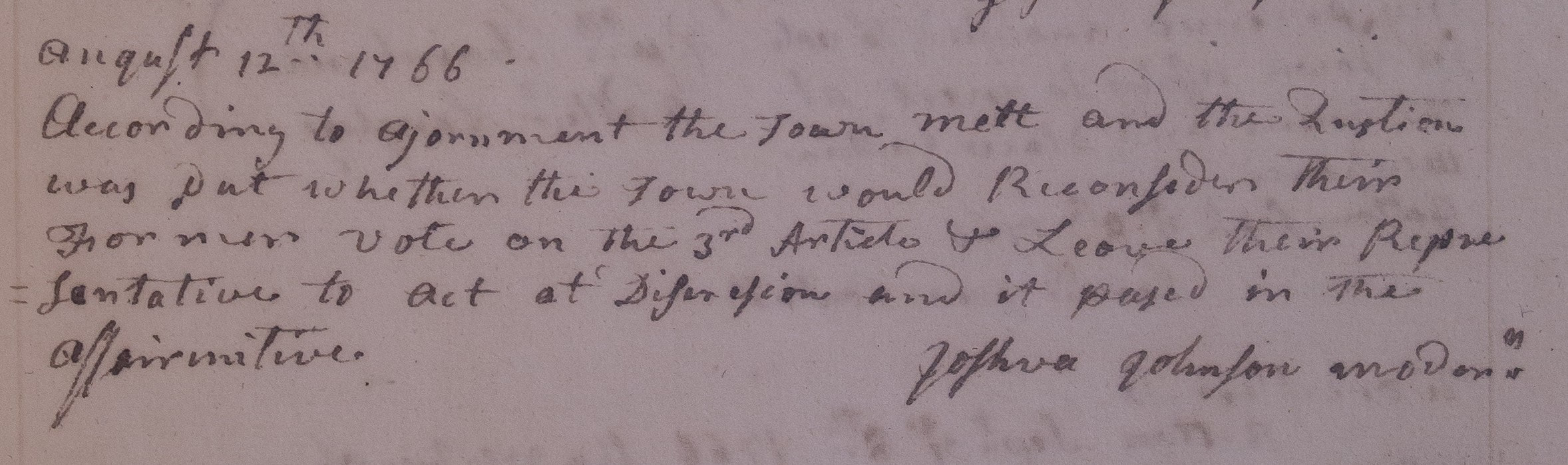

In response to making amends to crown officials for the Stamp Act riots, Bolton voted in the affirmative on article 3 at their July 15th town meeting: “to see what instructions the town will give their representative respecting making good the damages which sundry persons in the town of Boston received in the late disturbances by the mobs.” However, they had a change of heart and reversed their vote, for on August 12, 1766, the meeting minutes read “According to adjournment the town met and the question was put whether the town would reconsider their former vote on the 3rd article and leave their representative to act at disension (sic) and it passed in the affirmative.”

Bolton was no longer silent.

In 1763, no people were prouder to be British than the country folk of Massachusetts. The British were recent victors in the French and Indian War – a war in which many Bolton men fought. Now they were part of the world’s greatest empire, and they could claim all the prized liberties of English subjects. But, a dozen years later, they were at war again. Only now they were Americans, and their enemy was the British.

Trouble began in the Fall of 1765. To raise money to pay for the recent war, Parliament ordered that all printed materials bear a taxed stamp. This Stamp Act was fiercely resisted. Colonists declared it violated their ancient right to have a say in any taxation. In Boston, mobs rioted. On August 12th mobs attacked Andrew Oliver’s home, the Massachusetts government official responsible for enacting the Stamp Act, and twelve days later a mob ransacked the home of Lieutenant Governor Thomas Hutchinson. In Braintree, John Adams eloquently laid out colonial grievances, instructing representatives to denounce the Stamp Act. More than forty other towns followed suit. The town of Bolton had its share of men who resisted this taxation, but the Reverend Thomas Goss, Bolton’s minister, preached that the people must defer and submit to their betters. And so, on the Stamp Act, Bolton was silent.

In response to making amends to crown officials for the Stamp Act riots, Bolton voted in the affirmative on article 3 at their July 15th town meeting: “to see what instructions the town will give their representative respecting making good the damages which sundry persons in the town of Boston received in the late disturbances by the mobs.” However, they had a change of heart and reversed their vote, for on August 12, 1766, the meeting minutes read “According to adjournment the town met and the question was put whether the town would reconsider their former vote on the 3rd article and leave their representative to act at disension (sic) and it passed in the affirmative.”

Bolton was no longer silent.

In Response to the Townsend Act Bolton Sends a Delegate

The British greatly miscalculated the colonies’ reaction to the Stamp Act of 1765. It was met with fierce opposition; violent protests erupted and the cry “No taxation without representation” was heard throughout the colonies. Realizing that these protests and boycotts were damaging British trade; Parliament repealed the Stamp Act on March 18, 1766.

Within a year of the Stamp Act, Parliament tried again to find a way to pay for the expense of governing the American colonies. The Townshend Acts levied duties on many imported items, including paper, paint, lead, glass, and tea. The people of Boston expressed outrage at their town meeting. They signed an agreement to boycott these items and to encourage home manufacture in their stead.

In response, the men of Bolton met at the meetinghouse on Dec. 28, 1767 “to see what method the town will come into towards encouraging industry, frugality, and our own manufactures and also to return an answer to the Selectmen of Boston relating to the votes of the town of Boston which they communicated to us.”… “The town, taking into consideration a letter from the gentlemen selectmen of Boston and considering the publick spirit that appears therein by the inhabitants of Boston denying themselves their present and personal profits for the publick good, the inhabitants of the town of Bolton do most heartily concur with them in said proposal.” The town adopts these words unanimously; and on March 2, 1768, they met “To see what measures the town will come into for promoting Industry & Manufacturing among their inhabitants.”

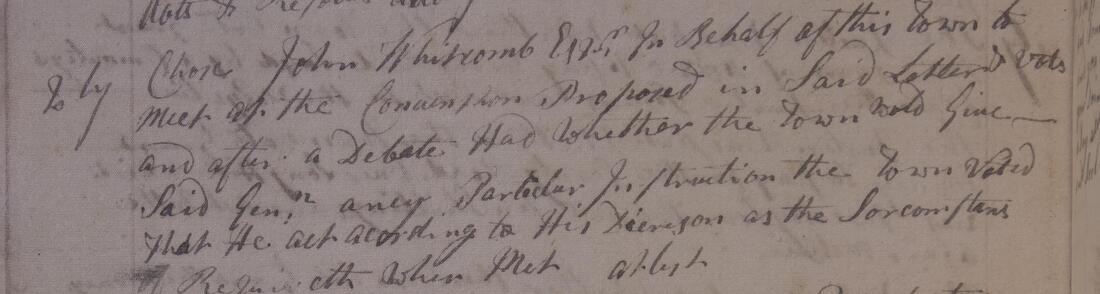

The response to the Townsend Acts was swift. Mobbing and violence erupted in Boston resulting in the British sending in troops to crack down on the rioting. Towns throughout Massachusetts were called on to elect representatives to assemble at a convention to be held at Faneuil Hall in Boston on September 22, 1768. The purpose was to air their grievances and to discuss how to handle the threat of the British troop arrival. This was a bold innovation. This assembly was not legal; those who went as delegates might be tried for treason, yet 96 of the colony’s 250 towns defiantly voted to send a representative anyway. Bolton “Chose John Whitcomb, Esq. on behalf of this town to meet at the convention.” The delegates who attended the convention met for a week; but the petitions they drafted to the governor and the king were scoffed at. John Whitcomb, Esq. would later go on to become the first major general of the Massachusetts provincial army.

Within a year of the Stamp Act, Parliament tried again to find a way to pay for the expense of governing the American colonies. The Townshend Acts levied duties on many imported items, including paper, paint, lead, glass, and tea. The people of Boston expressed outrage at their town meeting. They signed an agreement to boycott these items and to encourage home manufacture in their stead.

In response, the men of Bolton met at the meetinghouse on Dec. 28, 1767 “to see what method the town will come into towards encouraging industry, frugality, and our own manufactures and also to return an answer to the Selectmen of Boston relating to the votes of the town of Boston which they communicated to us.”… “The town, taking into consideration a letter from the gentlemen selectmen of Boston and considering the publick spirit that appears therein by the inhabitants of Boston denying themselves their present and personal profits for the publick good, the inhabitants of the town of Bolton do most heartily concur with them in said proposal.” The town adopts these words unanimously; and on March 2, 1768, they met “To see what measures the town will come into for promoting Industry & Manufacturing among their inhabitants.”

The response to the Townsend Acts was swift. Mobbing and violence erupted in Boston resulting in the British sending in troops to crack down on the rioting. Towns throughout Massachusetts were called on to elect representatives to assemble at a convention to be held at Faneuil Hall in Boston on September 22, 1768. The purpose was to air their grievances and to discuss how to handle the threat of the British troop arrival. This was a bold innovation. This assembly was not legal; those who went as delegates might be tried for treason, yet 96 of the colony’s 250 towns defiantly voted to send a representative anyway. Bolton “Chose John Whitcomb, Esq. on behalf of this town to meet at the convention.” The delegates who attended the convention met for a week; but the petitions they drafted to the governor and the king were scoffed at. John Whitcomb, Esq. would later go on to become the first major general of the Massachusetts provincial army.

The Circular Letter and Non-Importation Agreement

To protest the Townsend Act of 1767, Samuel Adams and James Otis of Boston wrote a letter to be circulated among all the towns stating that Great Britain had no right to tax the thirteen colonies without having representation in Parliament. Passed by the Massachusetts Assembly, the letter was circulated to not only the towns of Massachusetts but to the other colonies as well. Massachusetts towns large and small met to consider and responded. The Secretary of State of the colonies, Lord Hillsborough, fearing further protests, demanded that the Circular Letter be rescinded. In response, 92 members of the Massachusetts legislature stood up to the royal governor and refused to rescind the letter. Known as the Glorious 92, Bolton’s John Whitcomb was among them. To honor the Glorious 92, Paul Revere made a silver bowl, which is today on display at the Boston Museum of Fine Arts.

The royal governor did not find these non-rescinders glorious; he was infuriated. In response, he dissolved the Massachusetts General Court, which stayed closed from March 1769 until 1972. This action sent shock waves through the countryside. Many saw this as yet another dangerous infringement on their rights. Even more frightening, British troops arrived to be quartered in troublesome Boston. The countryside was not silent. Many protested the dismissal of their assembly and the arrival of British troops.

In reaction to the tax on goods enacted by the Townsend Act, Boston merchants and traders formed a Non-Importation Agreement to boycott goods that were subject to this Act until the taxes on those goods were repealed. Boston’s patriots now urged the towns to swear: “That we will not send for or import any kind of goods or merchandise from Great Britain, . . . from January 1, 1769, to January 1, 1770.” Some towns ignored this. Some mildly called to increase frugality. Others wholeheartedly embraced the boycott. Those who supported the boycott circulated covenants for their townsmen to sign; non-signers were treated as an enemy of the people.

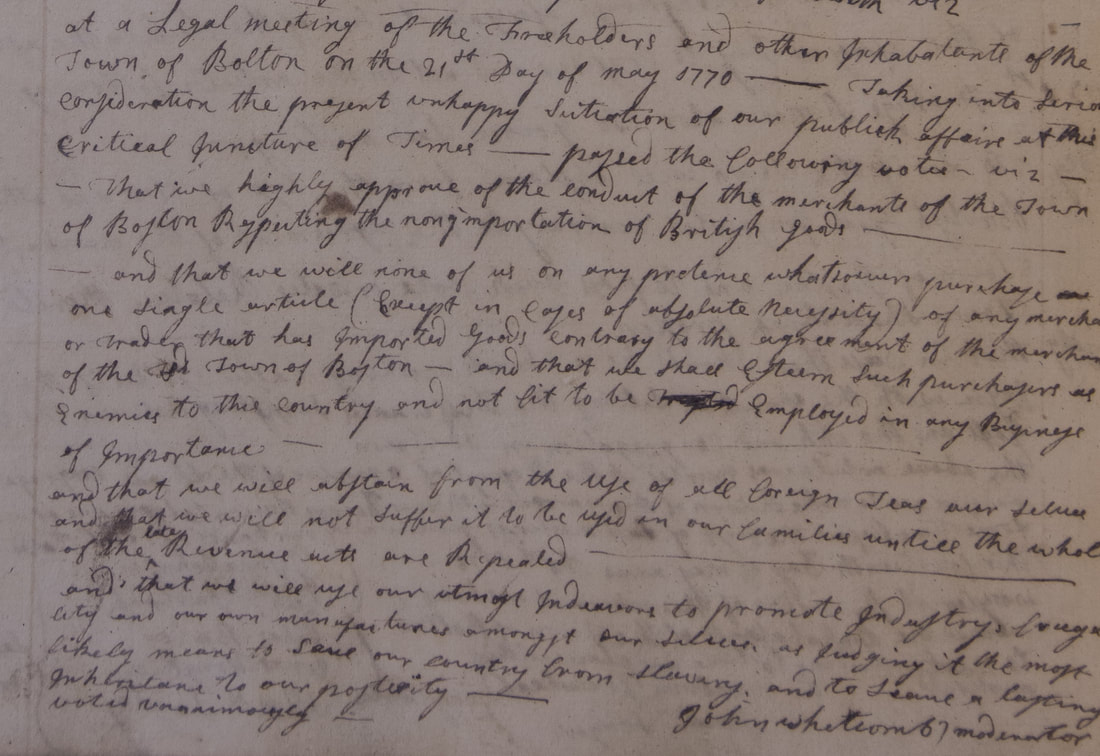

On May 21, 1770, Bolton spoke its mind: “That we highly approve of the conduct of the merchants of the town of Boston respecting the non-importation of British goods. And that we will none of us on any pretense whatsoever purchase one single article . . . of any merchant or trader that has imported goods . . . and that we shall esteem such purchasers as enemies to this country . . . And that we will abstain from the use of all foreign teas ourselves and that we will not suffer it to be used in our families until the whole of the late Revenue acts are Repealed. And that we will use our utmost endeavors to promote industry and frugality and our own manufacture amongst ourselves as judging it the most likely means to save our country from slavery and to secure a lasting inheritance to our posterity. voted unanimously. John Whitcomb, Moderator.”

The royal governor did not find these non-rescinders glorious; he was infuriated. In response, he dissolved the Massachusetts General Court, which stayed closed from March 1769 until 1972. This action sent shock waves through the countryside. Many saw this as yet another dangerous infringement on their rights. Even more frightening, British troops arrived to be quartered in troublesome Boston. The countryside was not silent. Many protested the dismissal of their assembly and the arrival of British troops.

In reaction to the tax on goods enacted by the Townsend Act, Boston merchants and traders formed a Non-Importation Agreement to boycott goods that were subject to this Act until the taxes on those goods were repealed. Boston’s patriots now urged the towns to swear: “That we will not send for or import any kind of goods or merchandise from Great Britain, . . . from January 1, 1769, to January 1, 1770.” Some towns ignored this. Some mildly called to increase frugality. Others wholeheartedly embraced the boycott. Those who supported the boycott circulated covenants for their townsmen to sign; non-signers were treated as an enemy of the people.

On May 21, 1770, Bolton spoke its mind: “That we highly approve of the conduct of the merchants of the town of Boston respecting the non-importation of British goods. And that we will none of us on any pretense whatsoever purchase one single article . . . of any merchant or trader that has imported goods . . . and that we shall esteem such purchasers as enemies to this country . . . And that we will abstain from the use of all foreign teas ourselves and that we will not suffer it to be used in our families until the whole of the late Revenue acts are Repealed. And that we will use our utmost endeavors to promote industry and frugality and our own manufacture amongst ourselves as judging it the most likely means to save our country from slavery and to secure a lasting inheritance to our posterity. voted unanimously. John Whitcomb, Moderator.”

Distracted: Bolton Fires Its Minister

Small irritations over the years between Bolton’s first minister, the Reverend Thomas Goss, and his congregation finally came to a head in 1771 when disagreement broke into the open. Goss was a man of the old school, educated and aristocratic. He expected his people to defer to his authority. But in the rebellious atmosphere of the times, some people of Bolton, particularly the plain-spoken but respected Col. John Whitcomb, resisted. They saw his manner as overbearing, his habits (especially his drinking) as immoral, and his views on deference to authority as out of touch with the times.

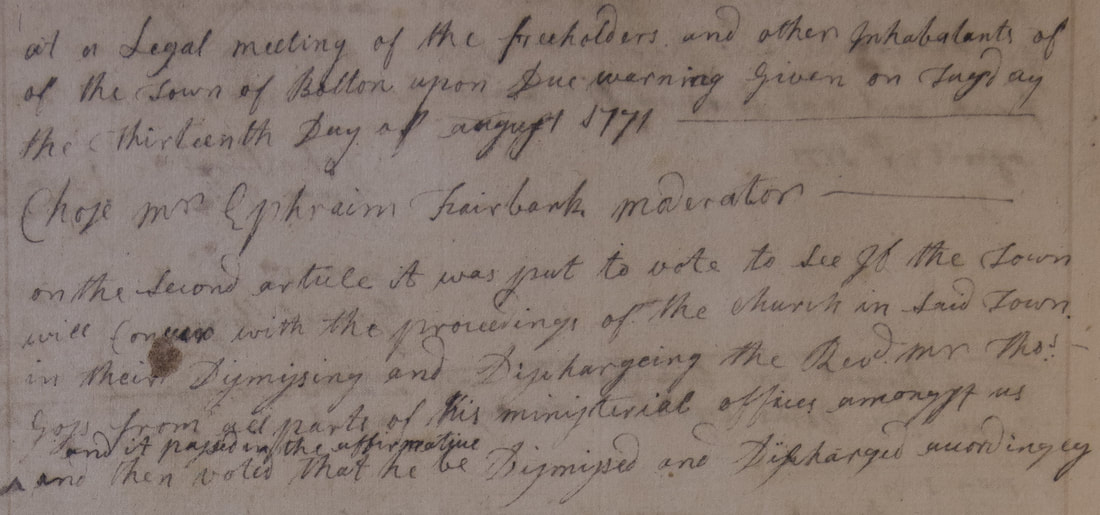

In July, a group of those who opposed Goss challenged his ministerial authority and gave reasons why he should be dismissed; and on August 13, 1771, the town voted that it is their opinion that “whereas Mr. Goss hath made a division in the church and by mal administration and breach of covenants hath brought the town into Deplorable Circumstances and thereby hath forfeited his right of claim to the desk as a teacher.” They have dismissed him from “all parts of his ministerial affairs amongst us.”

The challenge to their minister’s authority continued to distract the people of Bolton. The faction opposed to him forcibly barred him from entering the pulpit. Goss sued the town for his salary. A council of ministers from other towns urged the people of Bolton to forgive and take back their minister, but Bolton rejected this authority as well. The farmers of Bolton would no longer defer to those of learning, manners, or wealth. They had begun to define and defend the rights and liberties due all men. There has been speculation that Goss was a Loyalist; however, there is no evidence in the town books or other documentation to confirm this. His son, Thomas Goss, Jr., was a documented Loyalist and fled to Nova Scotia.

In July, a group of those who opposed Goss challenged his ministerial authority and gave reasons why he should be dismissed; and on August 13, 1771, the town voted that it is their opinion that “whereas Mr. Goss hath made a division in the church and by mal administration and breach of covenants hath brought the town into Deplorable Circumstances and thereby hath forfeited his right of claim to the desk as a teacher.” They have dismissed him from “all parts of his ministerial affairs amongst us.”

The challenge to their minister’s authority continued to distract the people of Bolton. The faction opposed to him forcibly barred him from entering the pulpit. Goss sued the town for his salary. A council of ministers from other towns urged the people of Bolton to forgive and take back their minister, but Bolton rejected this authority as well. The farmers of Bolton would no longer defer to those of learning, manners, or wealth. They had begun to define and defend the rights and liberties due all men. There has been speculation that Goss was a Loyalist; however, there is no evidence in the town books or other documentation to confirm this. His son, Thomas Goss, Jr., was a documented Loyalist and fled to Nova Scotia.

In 1772, a tone-deaf Parliament passed new measures to increase government power. Critically, the governor and all judges would now be appointed and paid directly by the Crown rather than by the people; local trial by jury would be replaced by courts under crown control. Patriots understood immediately that they had been stripped of popular checks on government authority. A town meeting was called in Boston to protest these new measures. Bostonians wrote an address to the governor expressing their concerns. They appealed to towns to support.

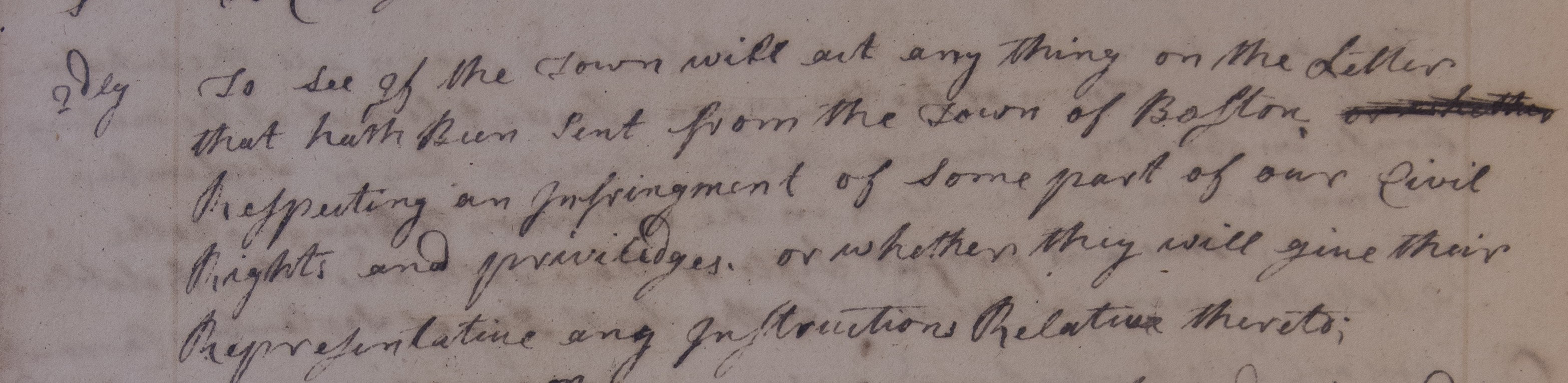

Bolton gave its support at the September 28th town meeting, “To see if the town will act anything on the letter that hath been sent from the town of Boston respecting an infringement of some part of our civil rights and privileges . . . voted that the infractions on the Rights and Liberties of the people of this Province as specified by the letter from the Committee of the town of Boston are great grievances and call for speedy redress and further voted that our representative be directed to use his best endeavors towards constitutionally addressing the same.”

The legislature presented an address with an appeal to redress grievances, but the governor refused to hear it.

Bolton gave its support at the September 28th town meeting, “To see if the town will act anything on the letter that hath been sent from the town of Boston respecting an infringement of some part of our civil rights and privileges . . . voted that the infractions on the Rights and Liberties of the people of this Province as specified by the letter from the Committee of the town of Boston are great grievances and call for speedy redress and further voted that our representative be directed to use his best endeavors towards constitutionally addressing the same.”

The legislature presented an address with an appeal to redress grievances, but the governor refused to hear it.

Bolton Forms a Committee of Correspondence and Defends Its Rights and Liberties

Parliament’s increasing control over the courts and its refusal to redress the colonists’ grievances led to Boston forming a twenty-one-member Committee of Correspondence whose purpose was to air grievances and to urge towns to spread the news of the British transgressions. Newspapers, pamphlets, and broadsides were common vehicles for getting the news out. Samuel Adams wrote a pamphlet reporting Boston’s resolves and sent it to all the towns. Known as the Boston Pamphlet, it called on each town to meet and assert the people’s rights. It also called for each town to form a Committee of Correspondence. These committees would share news of dangers and cooperate in defense. The Pamphlet requested each town to respond in writing. On July 15, 1773, Colonel John Whitcomb was chosen one of five men to form a “Committee of Correspondence to join with the Committee of Correspondence of the town of Boston.”

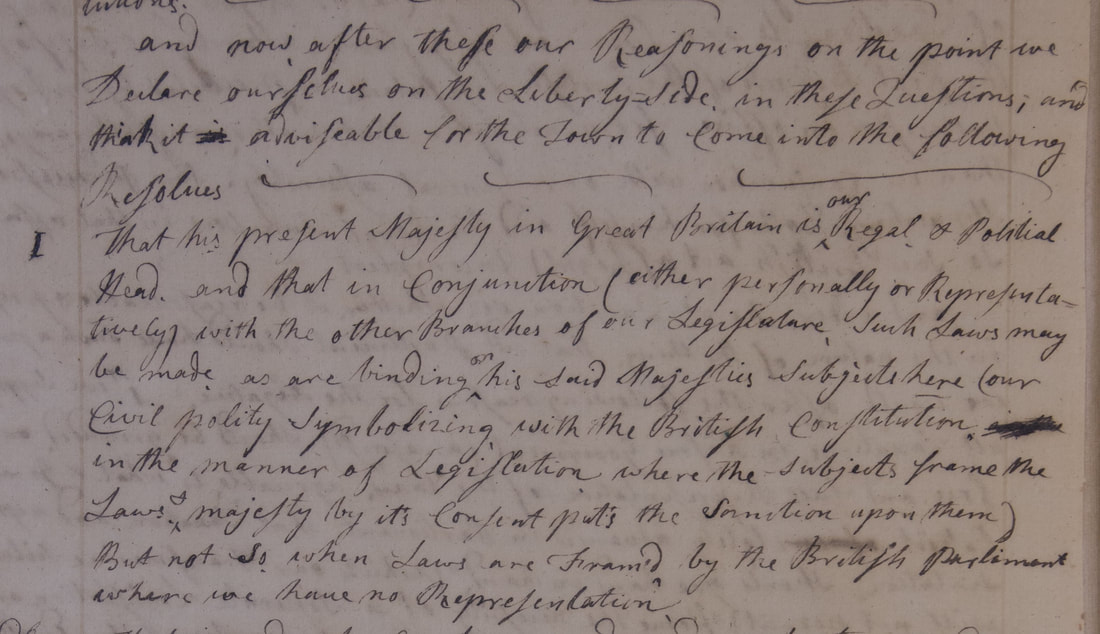

1773 turned out to be an anxious, angry year. In May, Parliament passed the Tea Act resulting in colonists disguised as Indians dumping tea from three ships into Boston Harbor on December 16th. Parliament was not amused, responding in the Spring of 1774 with harsh measures, they enforced the Intolerable Acts, closing the Port of Boston and quartering troops in private homes. Most alarming, they banned town meetings, stripping the towns of self-government. The Boston Committee of Correspondence immediately wrote to all the towns soliciting their advice and support. Bolton town meeting responded with a lengthy defense of their rights and liberties and then resolved on March 21, 1774: “We declare ourselves on the Liberty side in these questions . . .

1st. Laws may be made as are binding on his Majesties subjects here . . . but not when laws are framed by the British Parliament where we have no representation.

2ndly. That in order to counteract . . . the British act respecting the Duty on Tea to be paid here: we will not taste of this politically forbidden fruit . . .on any consideration whatever whilst it remains under this Circumstance of Taxation.

3rdly. That any persons purchasing and bringing any of said commodity into this Town . . . with an intent to use or vend it here, shall be deemed inimical to the Rights and Liberties of America and shall be excluded from all the honors and favours that is in the power of the Town to bestow.

By the late summer of 1774, the towns were afire with resistance. Many signed covenants pledging complete non-consumption of any imported British goods, and nasty consequences for those who did not comply. Bolton resolved on July 4: “it is the mind of this town that they will not purchase any goods imported from Great Britain (excepting medicinal Drugs) from and after the 31st day of August next.”

1773 turned out to be an anxious, angry year. In May, Parliament passed the Tea Act resulting in colonists disguised as Indians dumping tea from three ships into Boston Harbor on December 16th. Parliament was not amused, responding in the Spring of 1774 with harsh measures, they enforced the Intolerable Acts, closing the Port of Boston and quartering troops in private homes. Most alarming, they banned town meetings, stripping the towns of self-government. The Boston Committee of Correspondence immediately wrote to all the towns soliciting their advice and support. Bolton town meeting responded with a lengthy defense of their rights and liberties and then resolved on March 21, 1774: “We declare ourselves on the Liberty side in these questions . . .

1st. Laws may be made as are binding on his Majesties subjects here . . . but not when laws are framed by the British Parliament where we have no representation.

2ndly. That in order to counteract . . . the British act respecting the Duty on Tea to be paid here: we will not taste of this politically forbidden fruit . . .on any consideration whatever whilst it remains under this Circumstance of Taxation.

3rdly. That any persons purchasing and bringing any of said commodity into this Town . . . with an intent to use or vend it here, shall be deemed inimical to the Rights and Liberties of America and shall be excluded from all the honors and favours that is in the power of the Town to bestow.

By the late summer of 1774, the towns were afire with resistance. Many signed covenants pledging complete non-consumption of any imported British goods, and nasty consequences for those who did not comply. Bolton resolved on July 4: “it is the mind of this town that they will not purchase any goods imported from Great Britain (excepting medicinal Drugs) from and after the 31st day of August next.”

The Point of No Return: Massachusetts Forms a Provincial Congress

In the autumn of 1774, rumors abounded of starving people in Boston, British troops on the march, and the collapse of crown authority. Boston issued a call for a Massachusetts convention of town representatives to set up a new provincial government, independent of the crown.

While the “town of Boston is infested with troops and ships of war,” the king’s authority does not hold. And should that be the case, town meeting instructed our representative to “immediately repair to the Town of Concord and there join in a Provincial Congress . . . to act and determine in such measures as they shall judge proper to extricate this colony out of these present unhappy circumstances.” About two hundred towns responded, sending representatives to Concord in early October. Captain Samuel Baker and Ephraim Fairbank were elected to represent Bolton.

The Concord convention that met on October 11th embraced radical and treasonous measures. They sent representatives home with advice to raise money, men, arms, and ammunition. Towns were advised to raise new militia and elect new officers, loyal only to the authority of the people. The Convention called for 12,000 volunteers from the different towns, one-third of them who could be ready on a minute’s notice. Towns were counseled to ensure their militia were properly trained, armed, and disciplined to respond to any emergency.

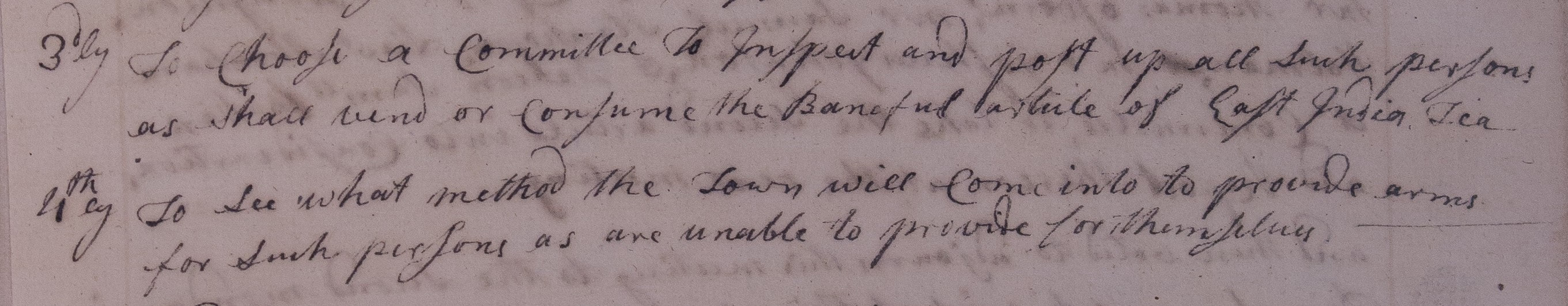

At the November 7th town meeting it was voted “To see what method the Town will come into to provide arms for such persons as are unable to provide for themselves.” Bolton, as a part of the Lancaster regiment, was already holding militia training at the Lancaster and Harvard training fields. Most of the men had their own guns with the town paying for the ammunition that was stored under the pulpit in the first Meeting House.

The Provincial Congress advised each town to set up a Committee of Safety to enforce boycotts of British good and act as a shadow government. These committees became a local police force, enforcing order and hunting down Tories. At that same November 7th town meeting, Bolton voted “to choose a Committee to inspect and post up all such persons as shall vend or consume the Baneful article of East India Tea.”

Continental Congress soon echoed Provincial Congress. It proposed a union government, the Continental Association, to regulate trade, advocate for rights, and keep order in the colonies since the collapse of royal authority.

On Dec. 12, 1774, Bolton was warned to meet and decide if it was to follow the advice and resolves of the Continental and Provincial Congresses to maintain good order. Dr Daniel Greenleaf was named to the town’s Committee of Inspection to police the community. To ensure their loyalty, all the men of Bolton were expected to sign a covenant or agreement to follow their rules of order.

Towns were instructed to pay their provincial tax not to the royal treasurer, but to a person appointed by the authority of the Convention alone. This was a bold challenge to royal authority. On Jan. 2, 1775, Bolton “voted that the money now in the constables’ hands that was made payable to Harrison Gray Esq. Provincial Treasurer . . .be paid to Henry Gardner Esq. of Stow agreeable to the advice of the Provincial Congress.” Bolton refuses to pay its taxes to the king.

While the “town of Boston is infested with troops and ships of war,” the king’s authority does not hold. And should that be the case, town meeting instructed our representative to “immediately repair to the Town of Concord and there join in a Provincial Congress . . . to act and determine in such measures as they shall judge proper to extricate this colony out of these present unhappy circumstances.” About two hundred towns responded, sending representatives to Concord in early October. Captain Samuel Baker and Ephraim Fairbank were elected to represent Bolton.

The Concord convention that met on October 11th embraced radical and treasonous measures. They sent representatives home with advice to raise money, men, arms, and ammunition. Towns were advised to raise new militia and elect new officers, loyal only to the authority of the people. The Convention called for 12,000 volunteers from the different towns, one-third of them who could be ready on a minute’s notice. Towns were counseled to ensure their militia were properly trained, armed, and disciplined to respond to any emergency.

At the November 7th town meeting it was voted “To see what method the Town will come into to provide arms for such persons as are unable to provide for themselves.” Bolton, as a part of the Lancaster regiment, was already holding militia training at the Lancaster and Harvard training fields. Most of the men had their own guns with the town paying for the ammunition that was stored under the pulpit in the first Meeting House.

The Provincial Congress advised each town to set up a Committee of Safety to enforce boycotts of British good and act as a shadow government. These committees became a local police force, enforcing order and hunting down Tories. At that same November 7th town meeting, Bolton voted “to choose a Committee to inspect and post up all such persons as shall vend or consume the Baneful article of East India Tea.”

Continental Congress soon echoed Provincial Congress. It proposed a union government, the Continental Association, to regulate trade, advocate for rights, and keep order in the colonies since the collapse of royal authority.

On Dec. 12, 1774, Bolton was warned to meet and decide if it was to follow the advice and resolves of the Continental and Provincial Congresses to maintain good order. Dr Daniel Greenleaf was named to the town’s Committee of Inspection to police the community. To ensure their loyalty, all the men of Bolton were expected to sign a covenant or agreement to follow their rules of order.

Towns were instructed to pay their provincial tax not to the royal treasurer, but to a person appointed by the authority of the Convention alone. This was a bold challenge to royal authority. On Jan. 2, 1775, Bolton “voted that the money now in the constables’ hands that was made payable to Harrison Gray Esq. Provincial Treasurer . . .be paid to Henry Gardner Esq. of Stow agreeable to the advice of the Provincial Congress.” Bolton refuses to pay its taxes to the king.

April 19, 1775

As proof of the Provincial Congress’ serious intentions, orders were given to the towns to stockpile arms, ammunition, and medical supplies to be prepared for the battle they were now certain would come.

Each man was expected to be fully armed at his own expense, although a few had guns supplied by the town. Their equipment consisted of a blanket, knapsack, gun, bayonet, a cutting sword or hatchet, flint, bullets, and buckshot, a powder horn and powder, tow for wadding and a quart-size canteen. They had no uniforms, wearing their everyday homespun garb; even the officers had no distinguishing uniforms in the beginning.

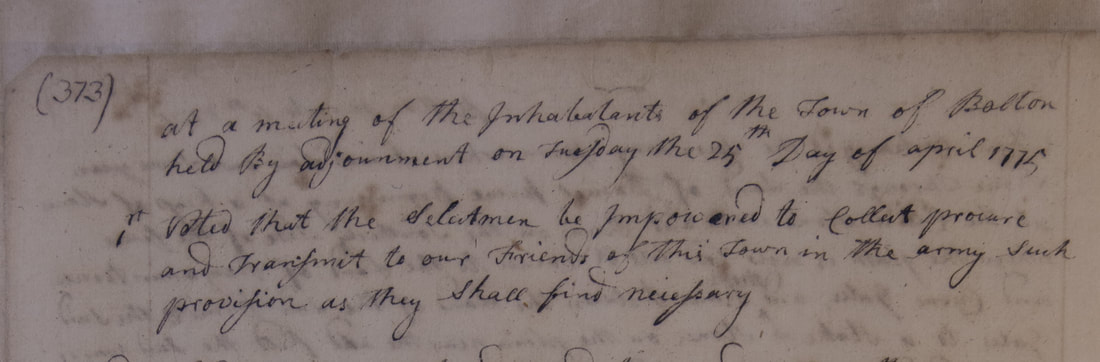

At a Town Meeting on April 10, 1775, Bolton “Voted to purchase ten guns for the use of those persons in this Town that are unable to purchase the same to be deposited in the hands of the Selectmen to be delivered out according to their discretion.” This meeting was adjourned until April 25th, but before that date, the alarm came in the early dawn of April 19th, and the town responded.

A notification system had been in effect for months so that in a very short time every member of the minutemen and militia knew that their services were needed. This was no casual response but had been planned long before.

Brothers John Whitcomb of Bolton and Asa Whitcomb of Lancaster, colonels of the two Lancaster regiments, were ready when the alarm came. John, who lived a few miles closer to Concord (his homestead stood at the corner of East End Road and Main Street) left immediately with his minutemen. His son John was directed to carry the warning to alert the company. Whitcomb had nine daughters, and it is said that some of them also helped to spread the alarm. There were no church bells to ring, but no doubt the drums did roll, and the minutemen were on their way. Colonel Asa Whitcomb, in charge of the militia, left as soon as his men could get assembled.

One hundred and twenty-seven men of the three companies from Bolton marched down the Great Road toward Concord. Colonel John Whitcomb and at least part of his minutemen were in the battle. Those who missed the fight continued on to Cambridge.

Imagine the sight: 763 men from the towns of Bolton, Harvard, Lancaster, and Leominster with more to follow from Lunenburg, Westminster, Ashburnham, and Fitchburg (the other towns which belonged to the Lancaster regiment) all marching down the Great Road through the center of Bolton toward Concord throughout that day and into the evening of the next day.

This war did not take the people of Bolton by surprise. They had spent the last ten years debating and asserting their rights, protesting, petitioning, boycotting, assembling, preparing, and resisting. They had come together to organize a provincial government, a treasury, a communication system, trained militia, arms, even popular police control.

They acted together as a town, and they made history.

Each man was expected to be fully armed at his own expense, although a few had guns supplied by the town. Their equipment consisted of a blanket, knapsack, gun, bayonet, a cutting sword or hatchet, flint, bullets, and buckshot, a powder horn and powder, tow for wadding and a quart-size canteen. They had no uniforms, wearing their everyday homespun garb; even the officers had no distinguishing uniforms in the beginning.

At a Town Meeting on April 10, 1775, Bolton “Voted to purchase ten guns for the use of those persons in this Town that are unable to purchase the same to be deposited in the hands of the Selectmen to be delivered out according to their discretion.” This meeting was adjourned until April 25th, but before that date, the alarm came in the early dawn of April 19th, and the town responded.

A notification system had been in effect for months so that in a very short time every member of the minutemen and militia knew that their services were needed. This was no casual response but had been planned long before.

Brothers John Whitcomb of Bolton and Asa Whitcomb of Lancaster, colonels of the two Lancaster regiments, were ready when the alarm came. John, who lived a few miles closer to Concord (his homestead stood at the corner of East End Road and Main Street) left immediately with his minutemen. His son John was directed to carry the warning to alert the company. Whitcomb had nine daughters, and it is said that some of them also helped to spread the alarm. There were no church bells to ring, but no doubt the drums did roll, and the minutemen were on their way. Colonel Asa Whitcomb, in charge of the militia, left as soon as his men could get assembled.

One hundred and twenty-seven men of the three companies from Bolton marched down the Great Road toward Concord. Colonel John Whitcomb and at least part of his minutemen were in the battle. Those who missed the fight continued on to Cambridge.

Imagine the sight: 763 men from the towns of Bolton, Harvard, Lancaster, and Leominster with more to follow from Lunenburg, Westminster, Ashburnham, and Fitchburg (the other towns which belonged to the Lancaster regiment) all marching down the Great Road through the center of Bolton toward Concord throughout that day and into the evening of the next day.

This war did not take the people of Bolton by surprise. They had spent the last ten years debating and asserting their rights, protesting, petitioning, boycotting, assembling, preparing, and resisting. They had come together to organize a provincial government, a treasury, a communication system, trained militia, arms, even popular police control.

They acted together as a town, and they made history.