|

EVANGELINE WILSON YOUNG: IRREPRESSIBLE ACTIVIST

Doctor, Teacher, Family Planning Advocate, Suffragette, Environmentalist, and Artist We would like to thank the family of Dr. Evangeline Young, her niece Marian Young Ingles, and great grandnieces Kathryn Marian Bawden and Paula Jeanne Bawden who donated these materials to the Bolton Historical Society in 1970. They are an extraordinary treasure that allows us to tell the story of a woman who wrote and spoke out strongly for what she believed in. |

|

A YOUNG GIRL FROM MAINE

She was born Evangeline Wilson Young on August 9, 1874 in Trenton, Hancock County, Maine to Captain Wilson Ryder Young and Melita Victoria Bartlett Young. When Evangeline was 12 years of age, her father, a sea captain, died while enroute to Brazil and was buried at sea, leaving behind his widow and eight children. We can only speculate that it was Evangeline’s experience of watching her mother struggle with supporting and keeping healthy eight children that led her to pursue a career in family planning. Seven of the Young children survived into adulthood; with baby Linda dying at 11 months. Evangeline at age 9 |

.Northfield Seminary for Young Ladies Class of 1896.

Identified on back of picture: 1 Mrs. Cox. 2 Marlin-Cornwall. 3 Innes-Falsh. 4 Hane. 5 Evangeline Young. 6 Galbraith. 7 Carr. 8 Chalmers.

Identified on back of picture: 1 Mrs. Cox. 2 Marlin-Cornwall. 3 Innes-Falsh. 4 Hane. 5 Evangeline Young. 6 Galbraith. 7 Carr. 8 Chalmers.

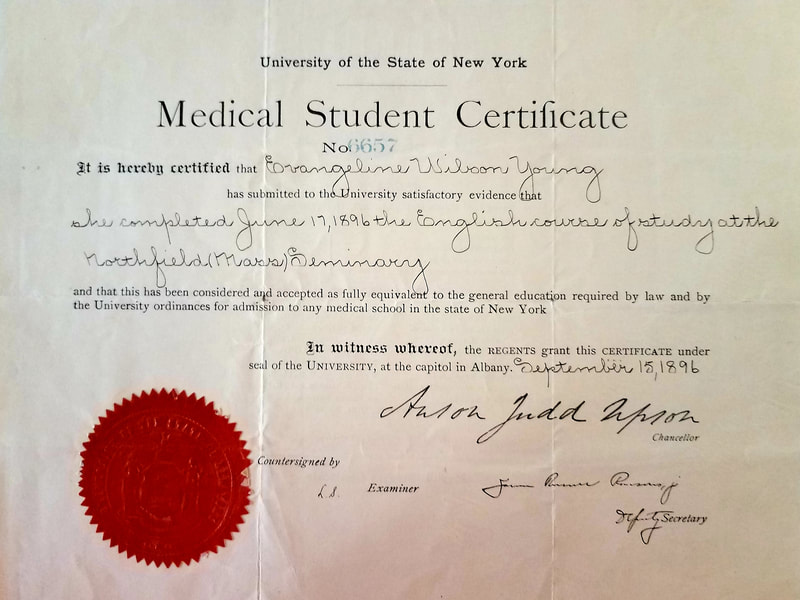

She received a Medical Student certificate from the University of the State of New York three months later, allowing her admission to any medical school in that state; although she put off attending medical school for a number of years, instead teaching in public schools in Bolton, Cambridge and Boston to raise money for medical school.

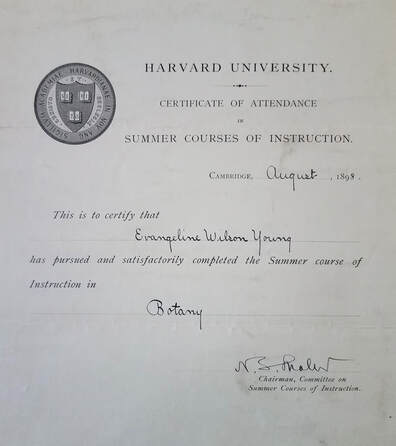

Her enrollment in a botany course at Harvard University shows an early interest in nature study. At a general meeting of the members of the Harvard Summer School in August 4, 1898, Evangeline spoke of the importance of the study of nature in the public schools: "There is much misunderstanding in the minds of some persons with regard to this work; they think it a waste of time to teach children about insects and flowers. A few weeks ago I was asked by a gentleman, who had spent the greater part of his life on the ocean, how I was intending to spend the summer. When I told him that I was intending to study botany at the summer school, he exclaimed, “They don’t expect you to teach that in the schools, do they? Teach flowers, indeed! Of what good is that?”

TEACHING IN BOLTON

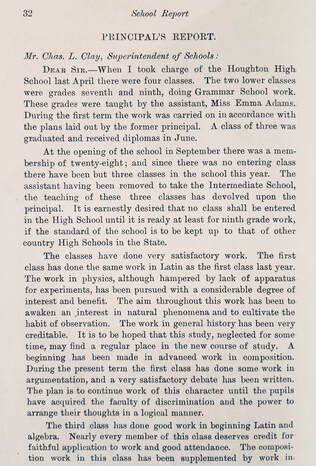

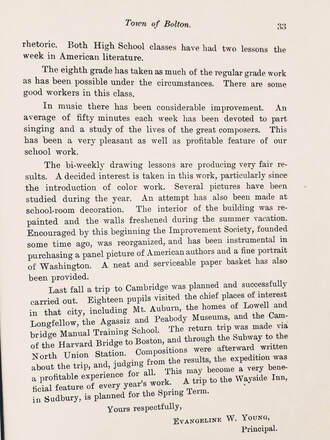

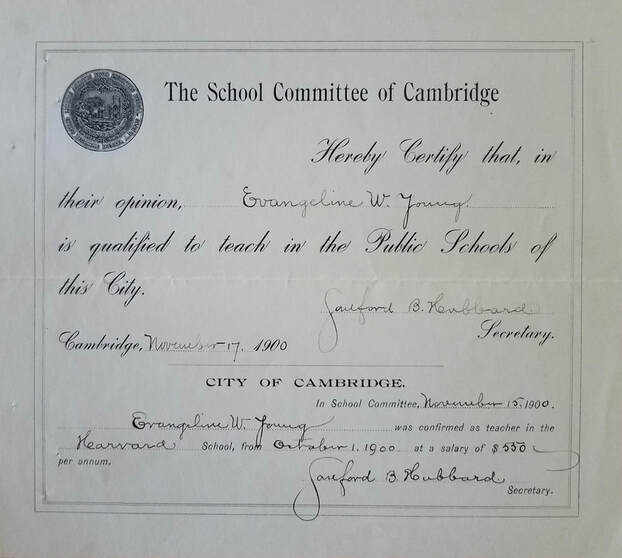

Evangeline arrived in Bolton in 1899 to assume her duties as principal and teacher at the Houghton School. She boarded at the home of Martha Stone Waite at 655 Main Street, a short walking distance from the school. She taught for only one year; in 1901, she accepted a teaching job in Cambridge for $100.00 more. If she had stayed in Bolton, she would have only been able to teach one more year because of a restriction in the will of Joseph Houghton, who donated the land on which the Houghton School was built and gave $12,000.00 to support a school, prevented teachers from staying longer than two years. It wasn’t until 1916 that the restriction was challenged and removed. She taught Latin, Algebra, Physics, History, English, Literature, Composition and Rhetoric, Music, and Drawing and led field trips to Cambridge and the Wayside Inn in Sudbury. Her salary was $450.00. Besides her duties at the high school, Evangeline was paid an extra $10.00 to teach drawing at the three primary and intermediate schools.

Evangeline arrived in Bolton in 1899 to assume her duties as principal and teacher at the Houghton School. She boarded at the home of Martha Stone Waite at 655 Main Street, a short walking distance from the school. She taught for only one year; in 1901, she accepted a teaching job in Cambridge for $100.00 more. If she had stayed in Bolton, she would have only been able to teach one more year because of a restriction in the will of Joseph Houghton, who donated the land on which the Houghton School was built and gave $12,000.00 to support a school, prevented teachers from staying longer than two years. It wasn’t until 1916 that the restriction was challenged and removed. She taught Latin, Algebra, Physics, History, English, Literature, Composition and Rhetoric, Music, and Drawing and led field trips to Cambridge and the Wayside Inn in Sudbury. Her salary was $450.00. Besides her duties at the high school, Evangeline was paid an extra $10.00 to teach drawing at the three primary and intermediate schools.

Houghton High School Class of 1890. Teacher Evangeline Young, wearing a straw hat, is in the back row center left

Evangeline's 1890 Principal's Report to the Town of Bolton:

Evangeline's 1890 Principal's Report to the Town of Bolton:

LEAVING AN INDELIBLE MARK

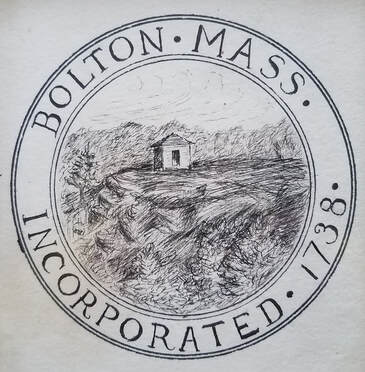

Like all “proper” ladies of her time, Evangeline was instructed in the art of drawing as a young girl. According to her niece Elizabeth Walker: “She loved to draw and often said, she would have liked to be a cartoonist.” And so it was that Evangeline drew something that left an indelible mark on the town of Bolton. Her drawing of the powder house was adopted as the official town seal in 1900.

Like all “proper” ladies of her time, Evangeline was instructed in the art of drawing as a young girl. According to her niece Elizabeth Walker: “She loved to draw and often said, she would have liked to be a cartoonist.” And so it was that Evangeline drew something that left an indelible mark on the town of Bolton. Her drawing of the powder house was adopted as the official town seal in 1900.

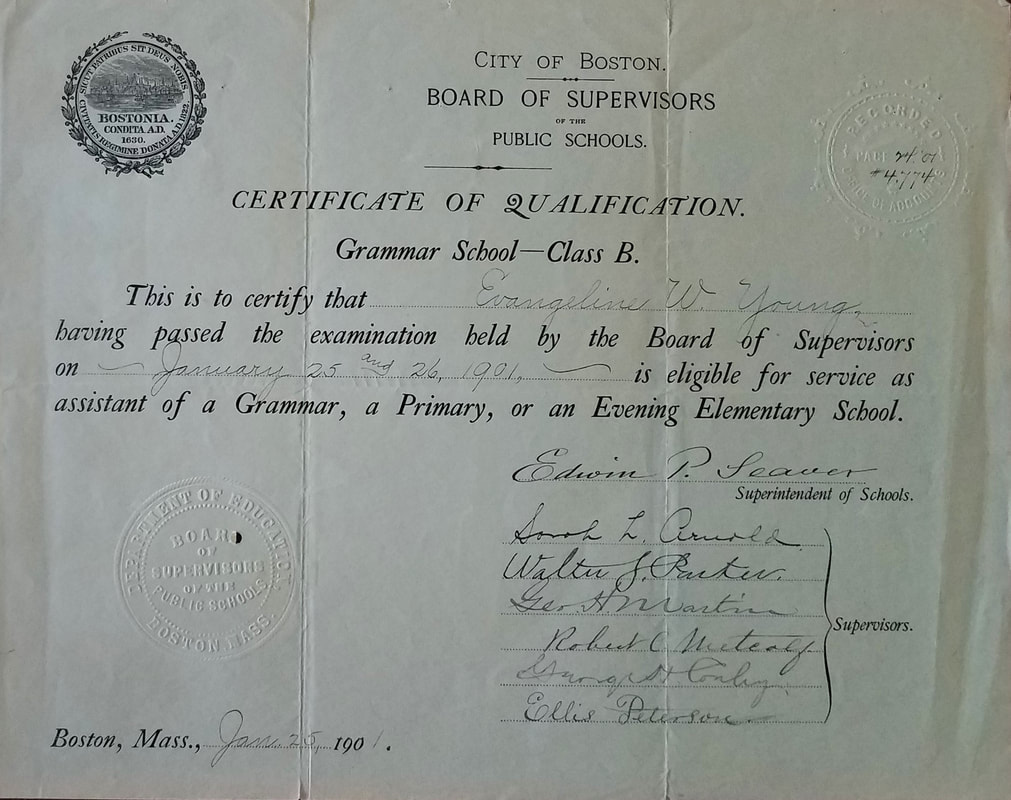

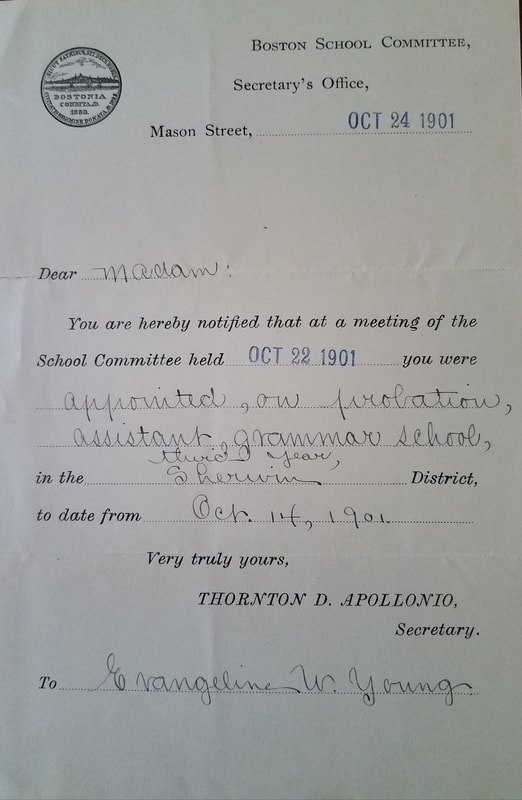

Leaving Bolton, Evangeline spent the next two years teaching in Cambridge and Boston. Below are her qualification certificates:

BECOMING A DOCTOR

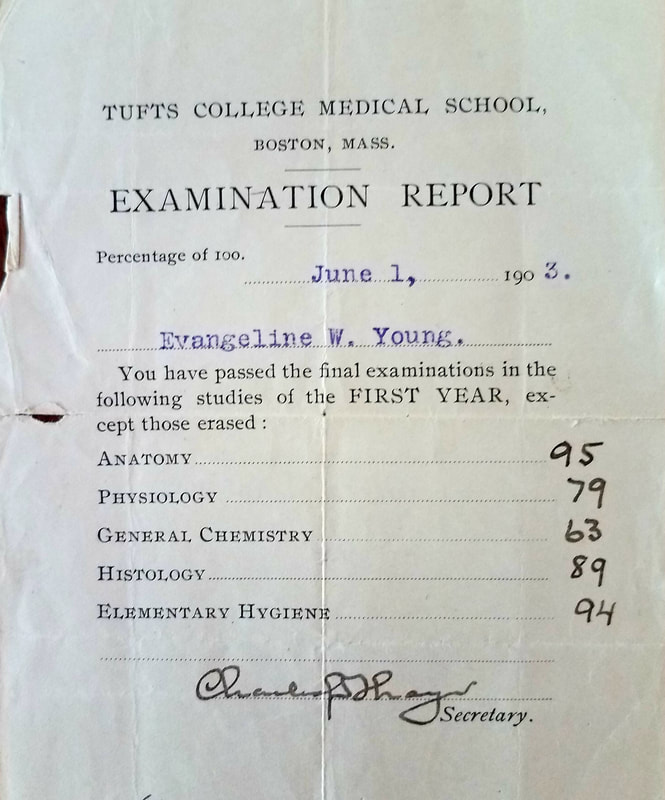

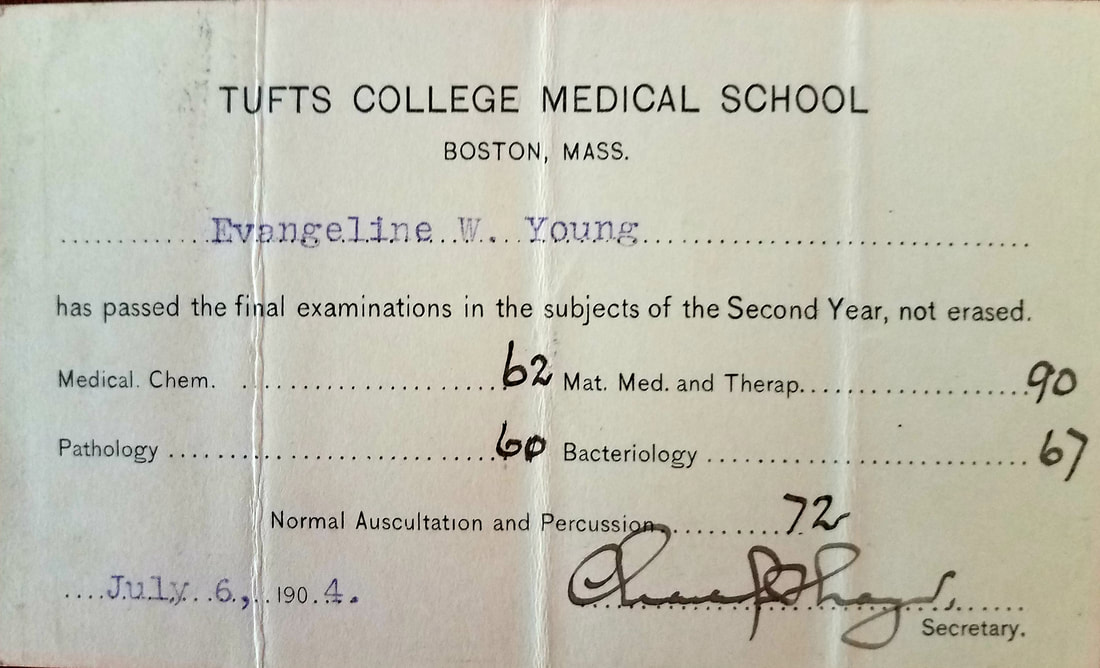

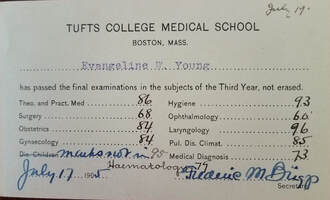

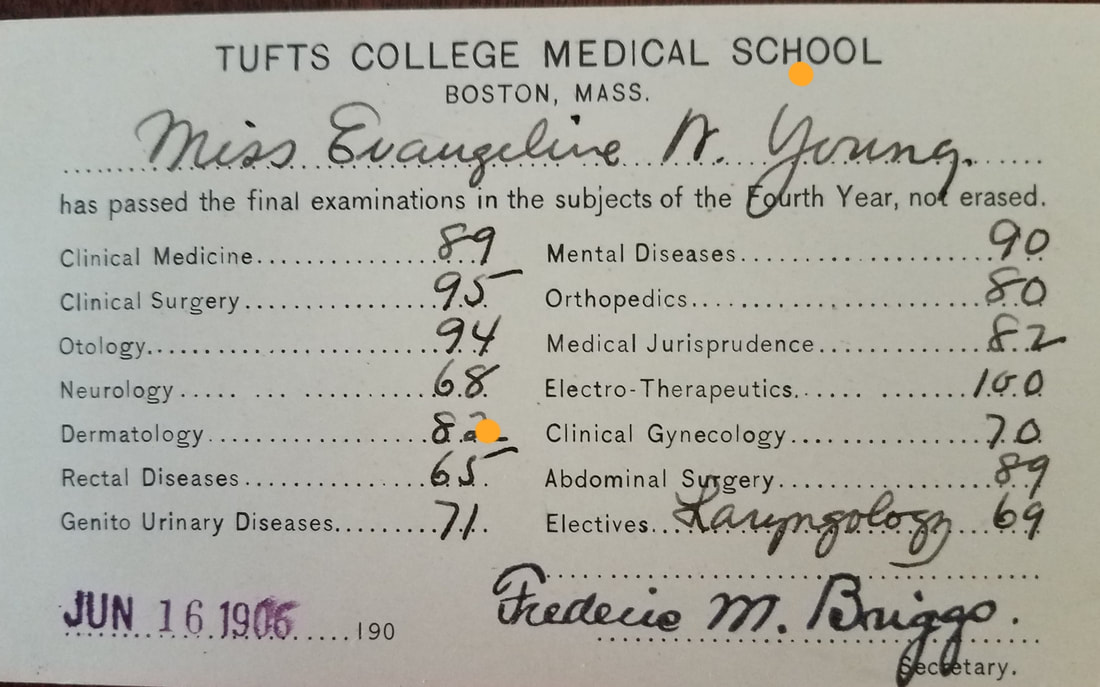

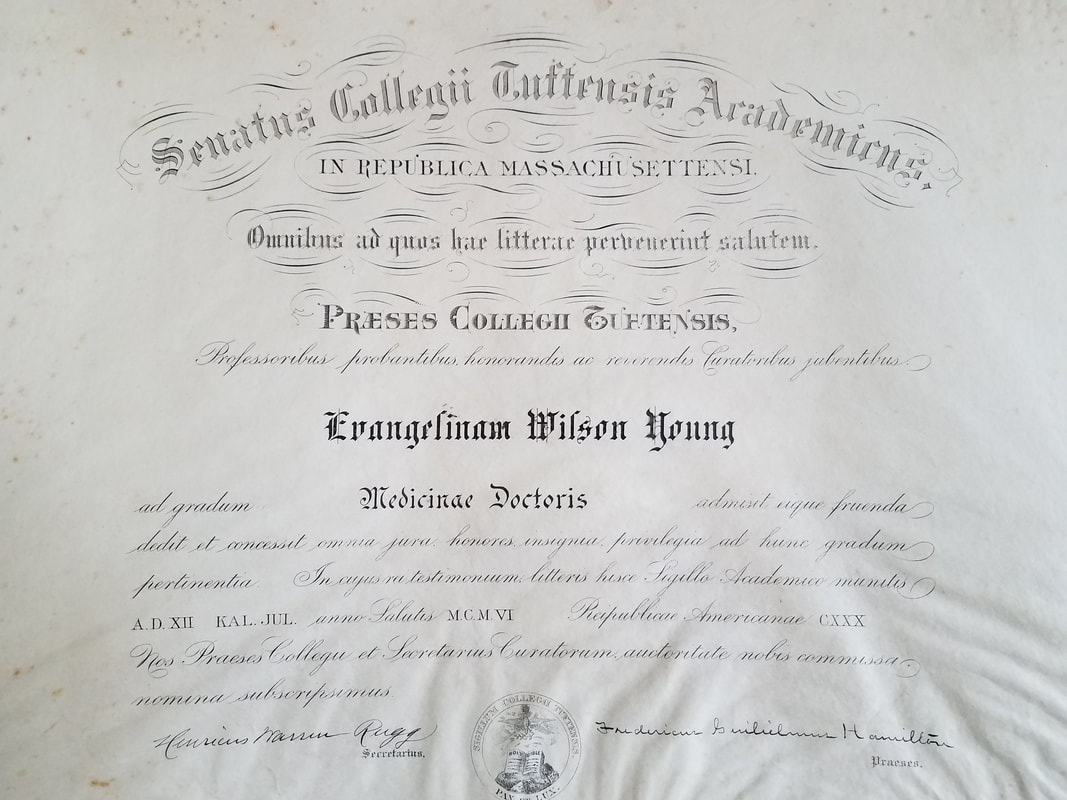

Her ambition to become a doctor was realized in 1902, when at the age of 28 Evangeline enrolled as a medical student at the Medical School of Tufts College, graduating four years later. The Medical School opened in 1893. It was coeducational from the beginning, with 22 students graduating in the first year; 8 of them were women.

Evangeline was entering medical school at a time when conservative Victorian attitudes toward female doctors were changing. The early 20th century saw better educational opportunities for women with more entering the workforce into jobs previously held by men only. By the end of the 19th century, 5 percent of the doctors in America were women, totaling over 7,000, with another 1,200 enrolled in medical schools. However, it still wasn’t easy for a woman to enter into jobs predominantly held by men; and discrimination existed in many forms. Describing her Aunt's struggle with discrimination, Evangeline’s niece Elizabeth Walker wrote: “She was, I think, positive and the rebuffs she had had to meet in making her way in a profession in a world of men, had hurt her deeply and gave the impression of formidableness at times but she did have a nicely developed sense of humor and fun."

Her ambition to become a doctor was realized in 1902, when at the age of 28 Evangeline enrolled as a medical student at the Medical School of Tufts College, graduating four years later. The Medical School opened in 1893. It was coeducational from the beginning, with 22 students graduating in the first year; 8 of them were women.

Evangeline was entering medical school at a time when conservative Victorian attitudes toward female doctors were changing. The early 20th century saw better educational opportunities for women with more entering the workforce into jobs previously held by men only. By the end of the 19th century, 5 percent of the doctors in America were women, totaling over 7,000, with another 1,200 enrolled in medical schools. However, it still wasn’t easy for a woman to enter into jobs predominantly held by men; and discrimination existed in many forms. Describing her Aunt's struggle with discrimination, Evangeline’s niece Elizabeth Walker wrote: “She was, I think, positive and the rebuffs she had had to meet in making her way in a profession in a world of men, had hurt her deeply and gave the impression of formidableness at times but she did have a nicely developed sense of humor and fun."

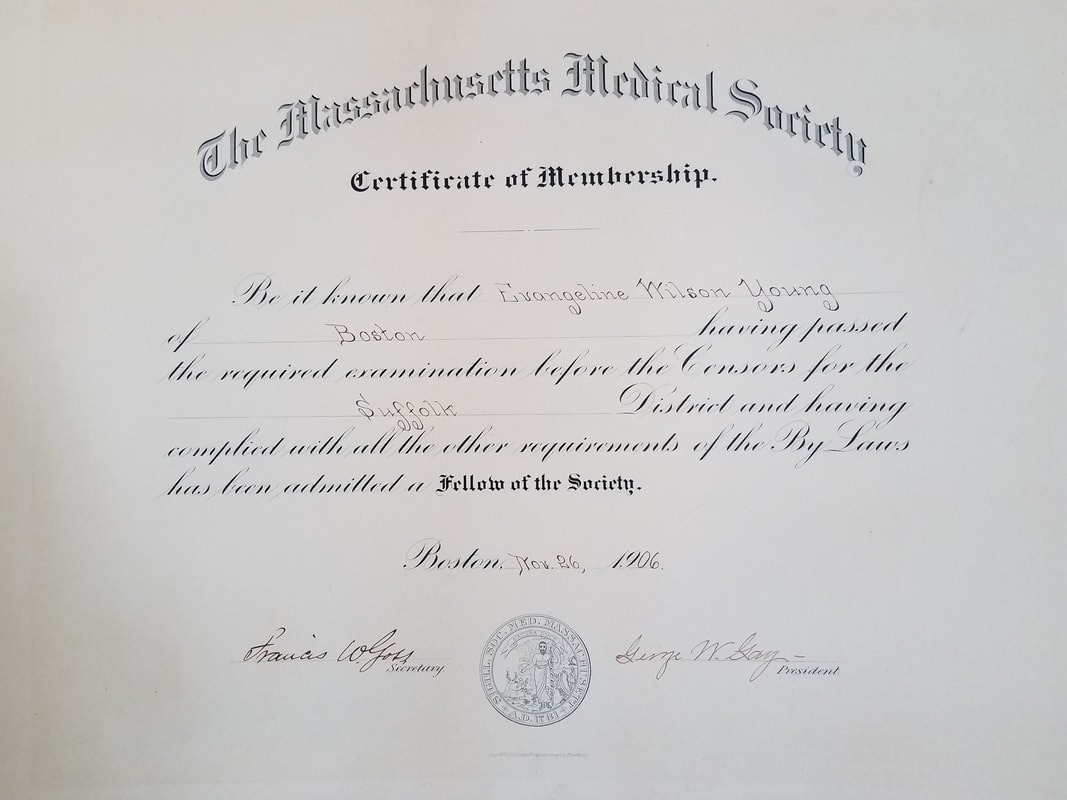

Following her graduation from Medical School, Evangeline began her practiced of general medicine in Boston, opening an office on Gainsboro Street. She became a well known doctor for women and children, opening a clinic for poor families and holding nutrition classes for mothers. Evangeline was known for her compassion and understanding toward her patients; according to her niece Elizabeth Walker: “she often went way out of her way to be helpful to her patients and they thought the world of her.”

Along with her practice, Evangeline lectured and taught courses at Simmons College, Dana Hall, Pine Manor, Wheelock College and the Garland School of Homemaking.

Below are transcribed letters from friends, students and patients to Evangeline.

Along with her practice, Evangeline lectured and taught courses at Simmons College, Dana Hall, Pine Manor, Wheelock College and the Garland School of Homemaking.

Below are transcribed letters from friends, students and patients to Evangeline.

Your browser does not support viewing this document. Click here to download the document.

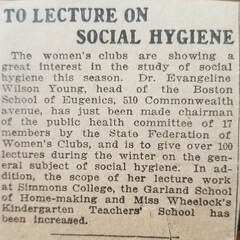

LECTURES

As a doctor, Evangeline was witness to the inequalities facing women from family planning, birth control, the need for sex education, poverty and rape to equal rights. Her first public lecture was at the Union Congregational Church in Boston in 1907; from then on she lectured around the country about family planning and birth control, and taught sex education in schools. She also expressed concern about overpopulation and pollution and campaigned for women’s right to vote. In a letter to a friend on the subject of her suffragette activity she wrote…”I fully expect that I may be jailed, but if necessary, I’m willing to go. We must win this fight.”

.

Attached are transcribed letters from groups and organizations requesting lectures and information:

As a doctor, Evangeline was witness to the inequalities facing women from family planning, birth control, the need for sex education, poverty and rape to equal rights. Her first public lecture was at the Union Congregational Church in Boston in 1907; from then on she lectured around the country about family planning and birth control, and taught sex education in schools. She also expressed concern about overpopulation and pollution and campaigned for women’s right to vote. In a letter to a friend on the subject of her suffragette activity she wrote…”I fully expect that I may be jailed, but if necessary, I’m willing to go. We must win this fight.”

.

Attached are transcribed letters from groups and organizations requesting lectures and information:

Your browser does not support viewing this document. Click here to download the document.

SCHOOL OF EUGENICS

We tend to think of eugenics in its negative form of racial and ethnic purity, but there also exists a positive form of eugenics. With the rise in social movements in the early 20th century and with women becoming better educated and independent, with expanding job opportunities and better information about marriage and sexual partners, positive eugenics became popular among middle class white women. In the article Dangerous Love: “Positive Eugenics, Mass Media, and the Scientific Woman, 1900-1945 by Natalie Parisa Oveyssi (Berkeley Undergraduate Journal, Volume 28, Issue 2): the lives of middle class women were improved by happier marriages, healthier children, superior parenthood and self-empowerment.

We tend to think of eugenics in its negative form of racial and ethnic purity, but there also exists a positive form of eugenics. With the rise in social movements in the early 20th century and with women becoming better educated and independent, with expanding job opportunities and better information about marriage and sexual partners, positive eugenics became popular among middle class white women. In the article Dangerous Love: “Positive Eugenics, Mass Media, and the Scientific Woman, 1900-1945 by Natalie Parisa Oveyssi (Berkeley Undergraduate Journal, Volume 28, Issue 2): the lives of middle class women were improved by happier marriages, healthier children, superior parenthood and self-empowerment.

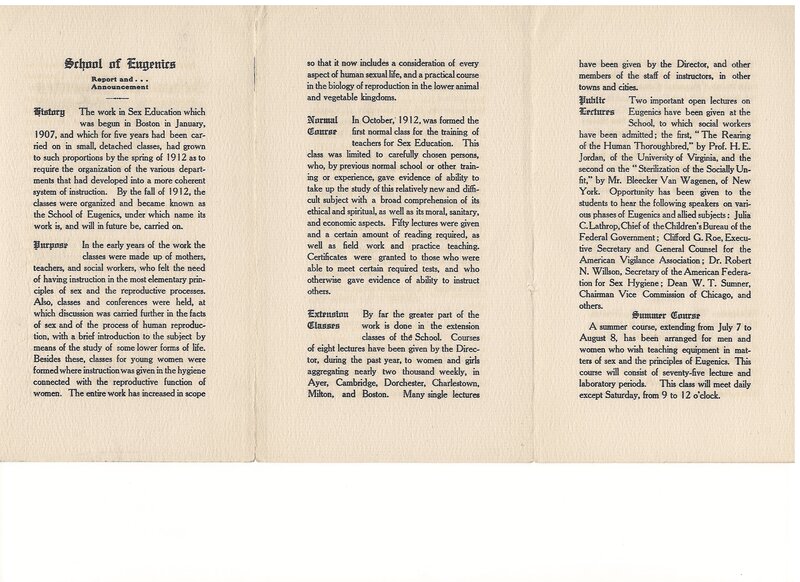

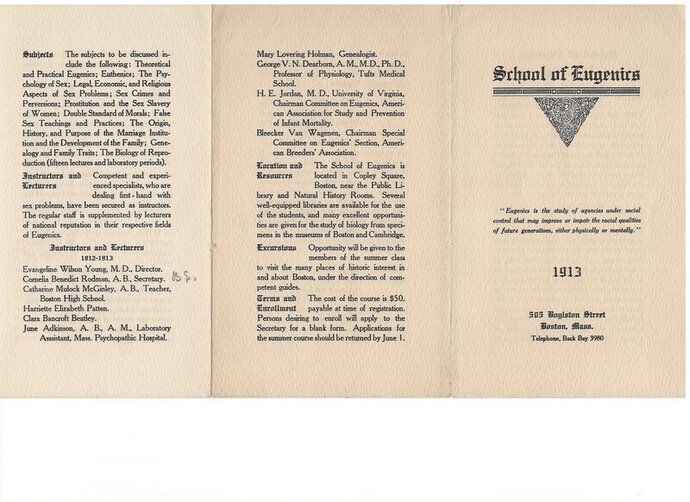

Evangeline embraced this movement, and was one of the first doctors to specialize in this field, becoming an authority in eugenics. Viewing marriage as science, she offered eugenic marriage consulting in her practice. As an outgrowth of the many lectures and courses held throughout New England, Evangeline opened the School of Eugenics in 1912. She served as director of the school for many years; it was later absorbed by Tufts University.

School of Eugenics Brochure, front, center fold and back:

School of Eugenics Brochure, front, center fold and back:

The Society holds reprints of three published articles and four lectures by Evangeline Wilson Young. The following transcription of a talk she gave to the American Society for the Prevention of Infant Mortality in Washington, D.C. is a good example of her belief in practical eugenics in which not only heredity but the environment are factors. This talk also highlights her views on physical hygiene, sex and marriage education, birth control and family planning.

Your browser does not support viewing this document. Click here to download the document.

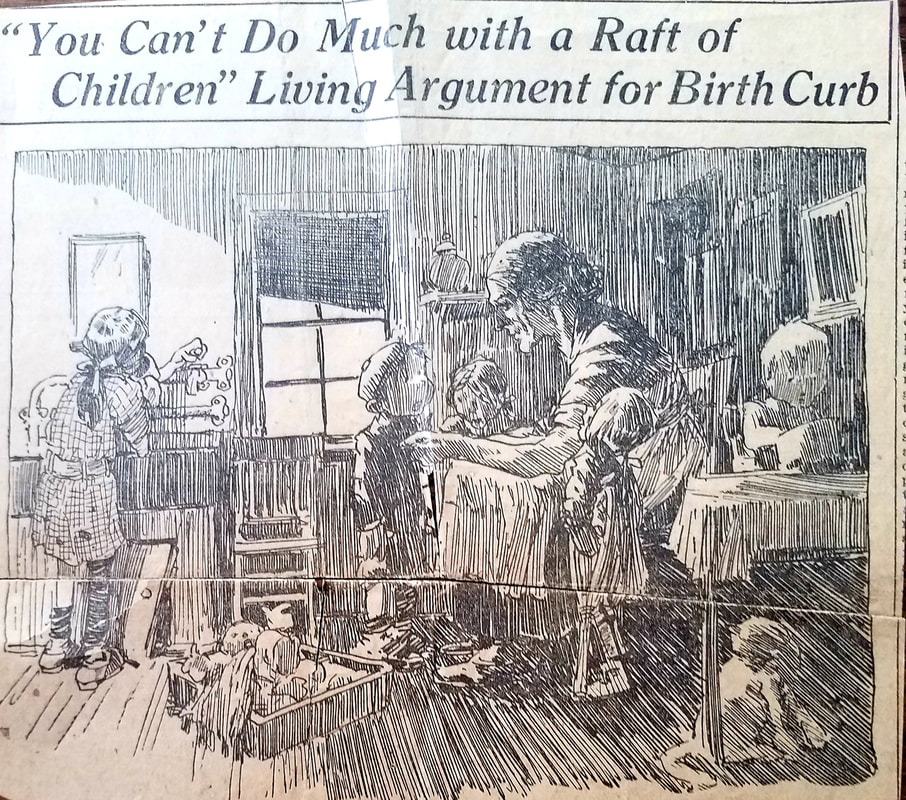

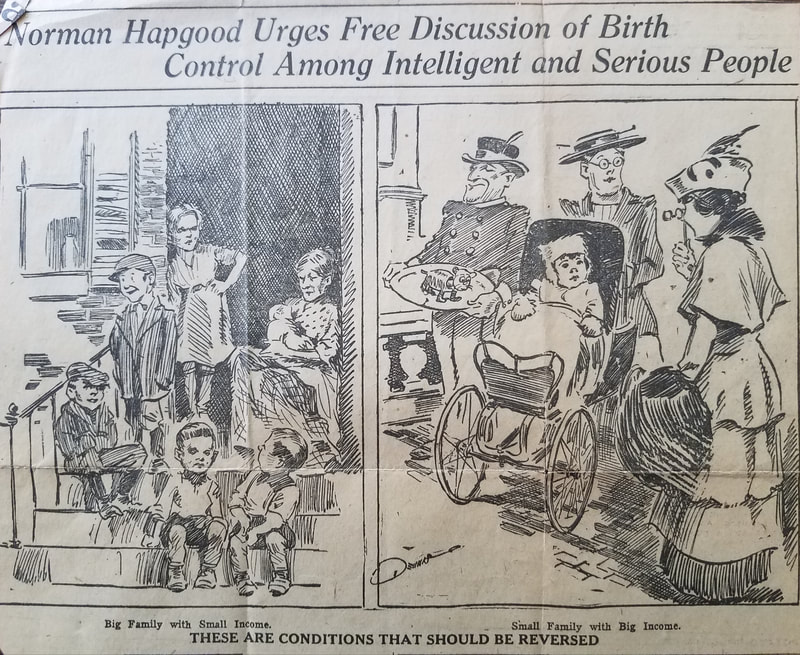

The social misfortunes of the overburdened mother with too many mouths to feed and an inadequate income to provide for proper nutrition and educational advantages was a central concern for Evangeline. The Society holds a number of newspaper clippings on birth control that she saved. The following drawings, both unsourced and undated, exemplify this topic.

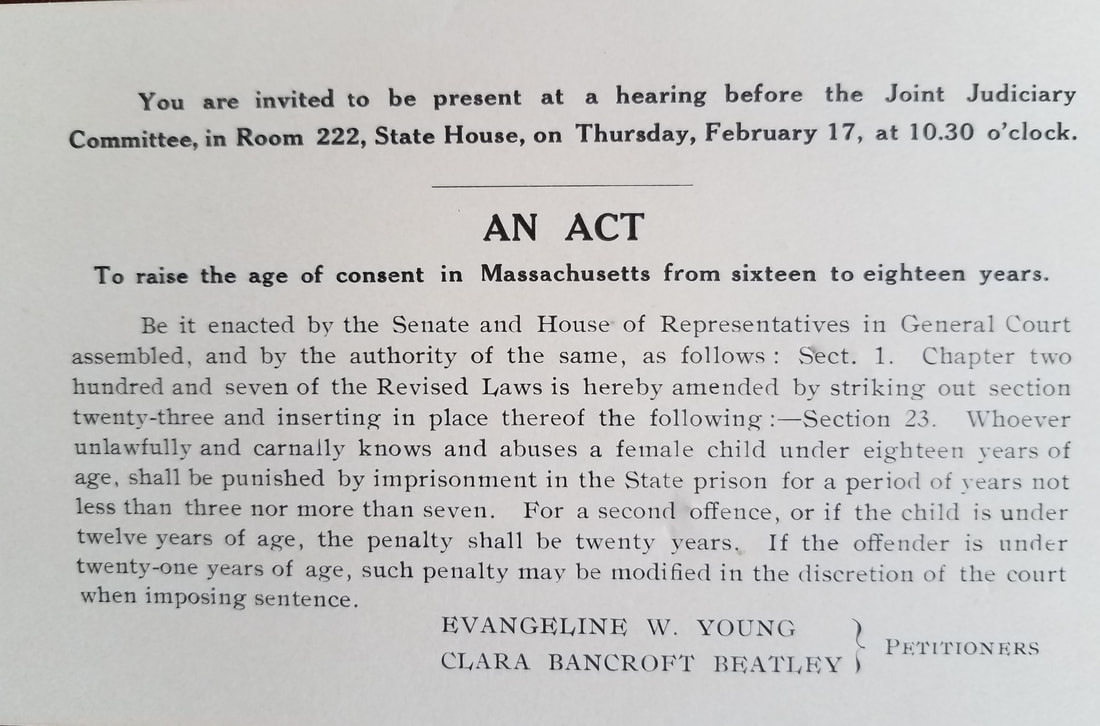

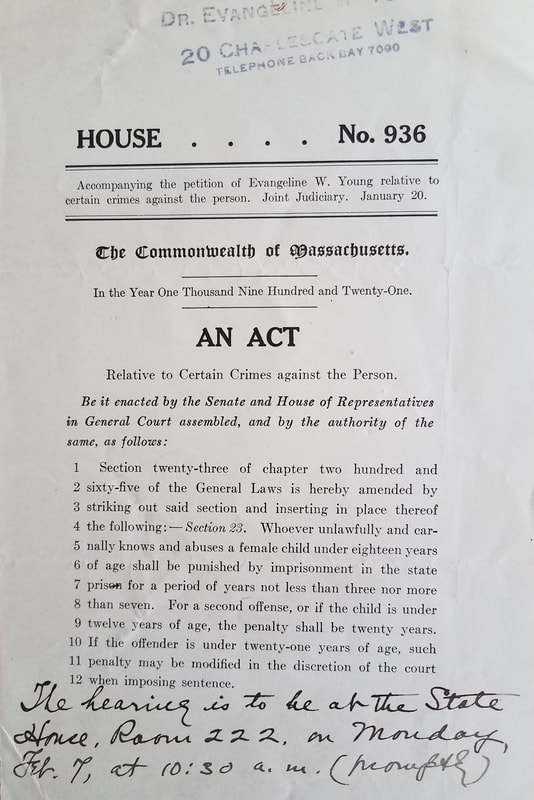

CHANGING THE LAW

Evangeline believed that women were treated as second class citizens under protection by law. In 1910 she petitioned the State legislature to raise the age of statutory rape from 16 to 18 years. She also stipulated that anyone found abusing a female child should be sentenced to 20 years in prison. Today, the age for statutory rape in Massachusetts remains at 16 and there is a penalty of a minimum of 10 years imprisonment for indecent assault or battery on a child 14 and under.

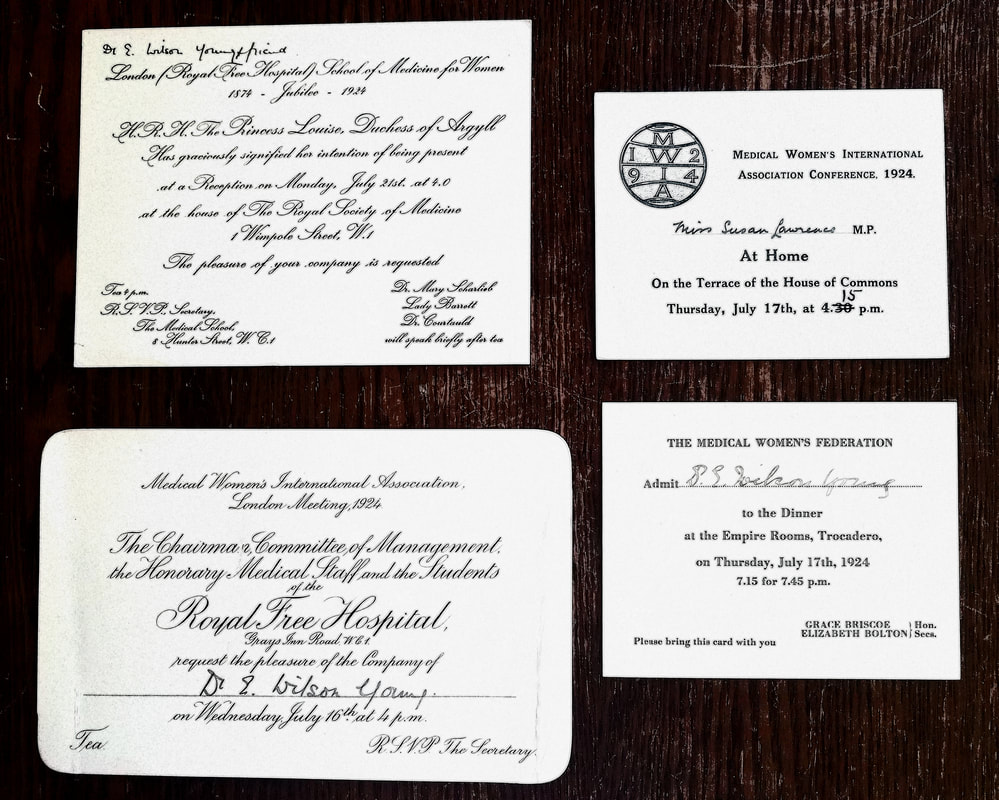

TRAVELING THE WORLD

In July of 1924, Evangeline traveled to London to attend the Medical Women’s International Association Conference. Below are several invitations to events for that conference:

In July of 1924, Evangeline traveled to London to attend the Medical Women’s International Association Conference. Below are several invitations to events for that conference:

LATER YEARS

Evangeline practiced medicine for 38 years. Besides administering to women and children she doctored disabled veterans from two world wars. Her writings were published in many magazines, including the Medical Review and the Women’s Medical Journal. Many of the courses that she taught were printed and distributed in all the states as well as abroad. She was known in the field of heart research and many of her articles on this subject can be found in Harvard and Tuft Universities’ medical libraries. She made innumerable contributions to the world of medical learning; and, her impact on Bolton with her design of the town seal will be everlasting. Dr. Evangeline Wilson Young died on December 20, 1944 and is buried at Mount Auburn Cemetery in Cambridge, MA.

Evangeline practiced medicine for 38 years. Besides administering to women and children she doctored disabled veterans from two world wars. Her writings were published in many magazines, including the Medical Review and the Women’s Medical Journal. Many of the courses that she taught were printed and distributed in all the states as well as abroad. She was known in the field of heart research and many of her articles on this subject can be found in Harvard and Tuft Universities’ medical libraries. She made innumerable contributions to the world of medical learning; and, her impact on Bolton with her design of the town seal will be everlasting. Dr. Evangeline Wilson Young died on December 20, 1944 and is buried at Mount Auburn Cemetery in Cambridge, MA.